Since the beginning of the year, I have been working on my personalized CS degree. Currently, I am working on MIT Course 6-001, which is an intro to programming. Expectedly, the lectures haven't been anything new to me, but I have still learned new things by adapting the problem sets written in python to TypeScript.

There is one problem set in particular that has tested my knowledge. In one of the problem sets, intended to help learn about looping, I wrote a solution using a trie data structure (pronounced "try"). Even though a regular student wouldn't know about this structure, I decided to use it to help me learn and understand it better. In the rest of this post, I will go over the trie data structure and its usefulness.

What is a trie?

A trie data structure is a data structure that is best used to optimize retrieving data. In fact, the name trie comes from the four letters in the middle of the word retrieval (reTRIEval). Simply put, a trie is a bunch of nested objects that efficiently store data.

The trie data structure is best understood with a use case. Let's say we want to have a list of current users on a website to search through. We want to show all valid users that start with what our user has typed so far as our user types. We could put it all in an array and search for it like this:

function getNames(namePart, validNames){

return validNames.filter(name=>\^rob\.test(name))

}

This is simple and easy to understand, but it can be rather inefficient to keep checking the entire array every time the user types a letter. This is especially true if the list of users becomes huge.

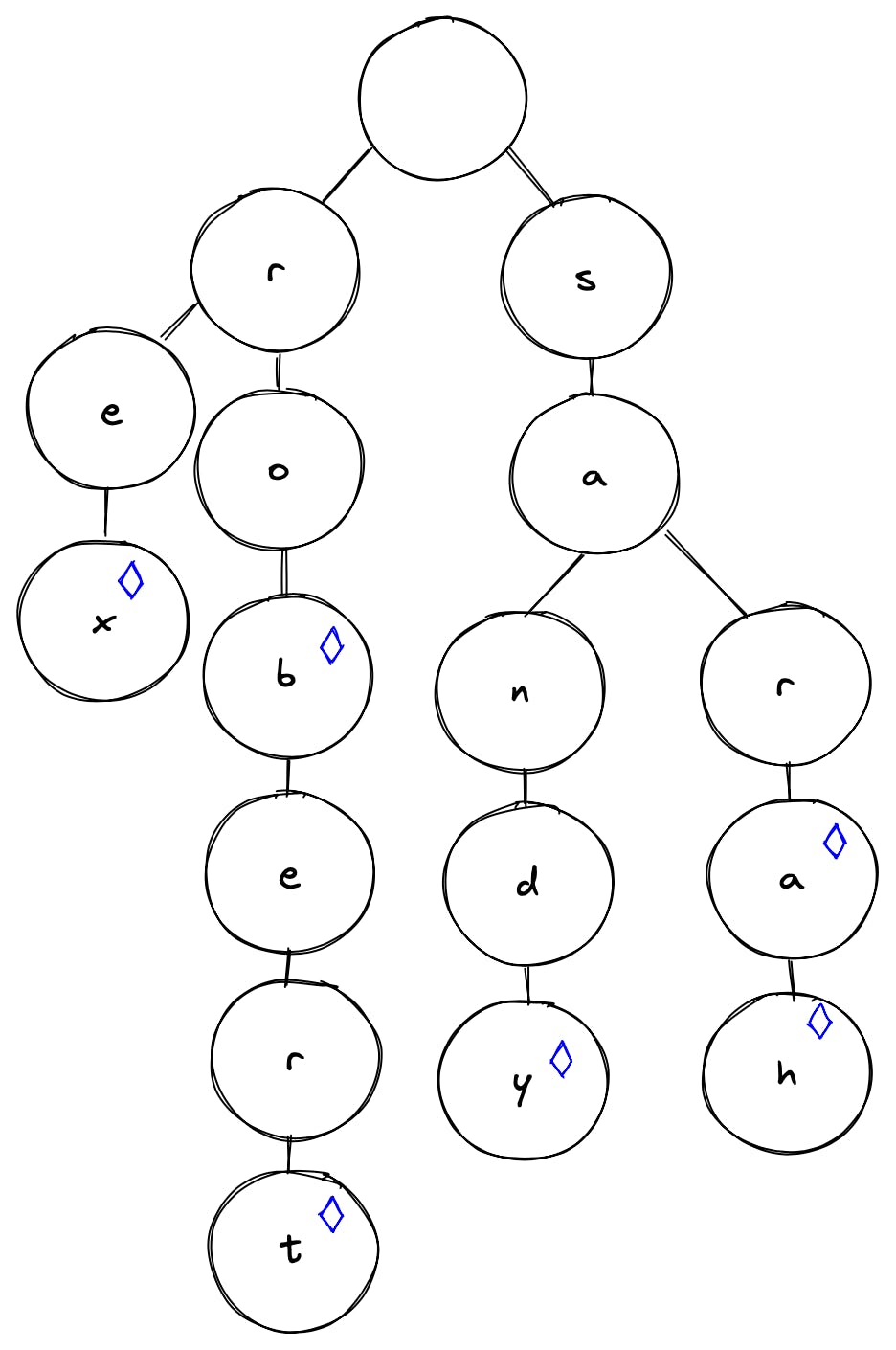

A trie takes advantage of the fact that we have overlapping string parts, and we can store them in a nested object that takes advantage of that. Let's say we have the following names: Sandy, Rex, Robert, Sara, Rob, and Sarah. We can put them in a trie that would look something like this diagram:

Each node represents a letter, with special markers on those nodes representing the end of a name. You can already see how efficient this is. As soon as you type one letter, you throw away 25 possible paths. We continue to narrow down the possibilities rapidly for each letter, drastically reducing the number of options as we go.

To implement a trie in JavaScript with just the name rex, it would look like this:

const trie = {

end: false,

children: {

r: {

end: false,

children: {

e: {

end: false,

children: {

x: {

end: true,

children: {},

},

},

},

},

},

},

};

This may not be very readable for a human, but it is beneficial to write code around. To add a word, we can traverse the tree, adding new nodes as needed along the way. The same is true for finding words. One needs to traverse the tree, finding all the children nodes that the end property is true

The specific problem

I needed to check if a user's input was a valid word in an array of words in the problem set. Normally I would do something like wordlist.includes(validWords). The problem is that once per word, a user can replace a vowel with the * wildcard character that could represent any vowel. In other words, c*t would match to cat, cot, or cut.

To do this with an array would be possible, but it would not be straightforward to read or write. Let's say we have converted the word list to a trie. We could easily write a lookup like this:

function checkIsValidWord(word, trieNode) {

if (word === "") return trieNode.end;

const nextLetters = word[0] === "*" ? "aeiou" : word[0];

const remainingWord = word.substring(1);

const defaultNode = { end: false, children: {} };

return nextLetters.split("").reduce((validWordFound, char) => {

const nextNode = trieNode.children[char] ?? defaultNode;

return validWordFound || checkIsValidWord(remainingWord, nextNode);

}, false);

}

The above function is a recursive function that takes a word and a trieNode. Since it is recursive, we start the function with a base case. If the string is empty, the trieNode passed in is the final node, and we can return the value at the end property.

If the word is not an empty string, then we do two things: grab the next character(s) to check and assign it to nextLetters. If the next character is *, we need to check the aeiou string. Otherwise, we check the next character. After that, we take the remaining part of the word as the next word to check. Otherwise, we will just check the next letter.

After that, we split the nextLetters string into an array of characters. We reduce that array of characters by checking if we have found a valid word yet, and if not, we call the checkIsValidWord function with the remaining characters and the node of the character we are checking.

By adopting a data structure design for what we want to do, we have made both an efficient and elegant solution for a potentially complicated problem.